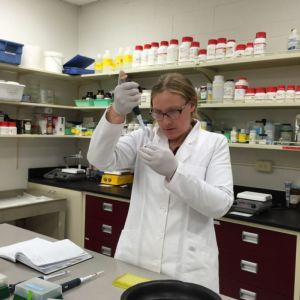

For biotechnology student Kim Lantrip the thrill of participating in scientific discovery happened during the second semester of her biotech program at Flathead Valley Community College.

The molecular procedure for identifying wildlife species that she and classmate Brad Dixon devised and tested during spring 2015 semester is helping to determine whether Canada lynx and wolverine, two threatened species, are living in the Lost Trail National Wildlife Refuge in Montana. The animals have been seen, but a wildlife biologist needs physical evidence to seek "critical habitat" designation of the 7,885-acre refuge.

"It's incredibly motivating, because I'm doing something that has obvious implications. I can assist this range in becoming a critical habitat, which would then help the animals," Lantrip explained last week in Washington, D.C. She was among the 60 students from across the U.S. and Guam who shared their learning experiences at the 2015 Advanced Technological Education Principal Investigators Conference in Washington, D.C., October 21 to 23.

The laboratory procedure that Lantrip and Dixon developed first isolates the mitochondrial DNA from fur left by the animals whose bodies rub along the fur traps placed at the direction of Beverly Skinner, a wildlife biologist at the refuge.

For help to identify fur samples to confirm the presence of a lynx population Skinner contacted Ruth Wrightsman, a biology instructor at FVCC and the principal investigator of an ATE grant that supported development of the biotechnology transfer degree program at the rural college. In 2002 the college received a MentorLinks grant from the American Association of Community Colleges to strengthen its natural resources programs. Both the ATE grant and the MentorLinks grant were funded by the National Science Foundation.

Wrightsman made the biologist's question a project for her spring Biotechnology 205 course. The major assignment was coming up with an accurate, repeatable molecular method for identifying wildlife species.

Figuring Out Process for Reliable Test

"It's harder than it sounds," Lantrip said with a chuckle. Well, actually it sounds hard too. Here's how Lantrip described what she and Dixon worked out in the college lab using an animal tail that Skinner provided.

"The fur is left on a fur trap. Then we take it, and lyse the fur.

"You want the cells to break open and release the DNA, specifically the mitochondrial DNA.

"After that happens we run PCR [polymerase chain reaction] on the sample DNA, which gives you many, many copies of the target DNA sequence, COX1. [cytochrome oxidase 1, a gene present in all mammals.]

"We run PCR on the thermocycler. Then we run a gel electrophoresis. Then compare their DNA sequences with marker DNA."

Lantrip's poster for the showcase session at the conference included a photo of the microscopic sample that matched and a few that did not yield anything. This led to a discussion of the trial and error and modifications made to the tissue kit that were done in order to obtain sufficient quantity and quality PCR product with 700 base pairs (the length of the COX1 gene) to ship to a California lab for sequencing.

When the lab sent the gene sequence back with the computer code of "all these As and Ts and Cs and Gs," Lantrip and Dixon put data into the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website for bioinformatics analysis.

"We put this in NCBI and we got this amazing answer: You have an American Red Squirrel tail. No lynx. But the procedure worked," she said of the test procedure with results that matched what the biologist knew.

Working on Next Steps in Pursuit of Evidence

"Cementing" the procedure before working on unknown animal samples was an important step.

"The fur that's left on the fur traps, sometimes it's three or four hairs. So if you run these hairs and you don't get any results well there is a very important sample that could have been lynx that we just wasted because we didn't have a procedure down," she explained.

Now Lantrip works on real samples from the refuge as an independent study project.

The wildlife cameras recently set up along with the traps, which are designed to attract the lynx without harming them, recorded photos of what could be wolverines. They are also threatened. So checking for their DNA is now part of the protocol.

She considers the 100 hours invested in the project during the spring a good start toward gaining competency with biotechnology lab tasks.

"This procedure, doing all this—the problem solving, going through this whole process, taking so long— it's just made me realize how much I love working in the lab and how I thoroughly enjoy being given a problem and then solving it."

Subscribe

Subscribe

See More ATE Impacts

See More ATE Impacts

Comments

There are no comments yet for this entry. Please Log In to post one.